Posters

Maria Elorza

Luke Waller

Transcript

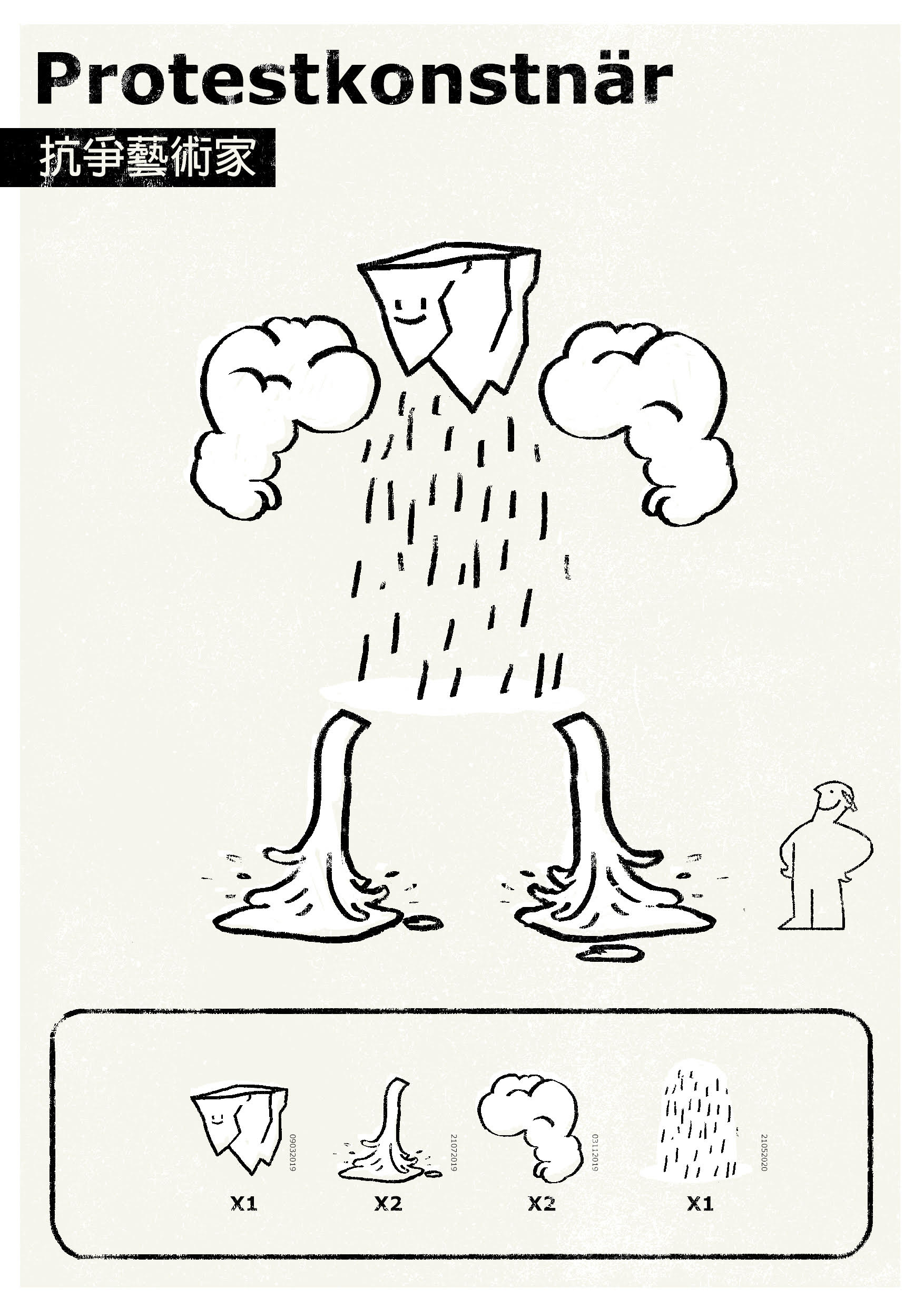

When Visiting Hong Kong during their recent pro-democracy protest, I was struck by the sheer volume of illustration used and how important a role it seemed to play within the movement. Roles for illustrators included documenting important events, negative or positive. Sign posting towards places to gather online or in the real world. Bringing people together or fostering positive energy as well as rallying calls. The spirit of the movement and its ‘Be Water’ message was reflected in the work of these illustrators, designers and makers.

I also want to mention intertextuality which greatly informed my response. Intertextuality was used particularly in reference to western culture to not only gain the attention of the west but to also bring comical relief to an incredibly tough subject. This further garners support for the movement so has been a focal point of my research.

My submission highlights the connections between intertextuality and the idea of learning from the protest in Hong Kong. By using the widely recognisable signs of an IKEA instruction manual in combination with the core principles of the ‘Be Water Movement’ I am able to pinpoint the focus of my research as well as the new direction that I have been looking at as a result. Namely Daoist philosophy and what new perspectives that might give us as illustrators connected with protest.

Rachel Davey

Marcus Diamond

Louise Bell

Gabrielle Brace Stevenson

Transcript

This poster is a tiny morsel of my practice as research (Barret 2007a), a work in progress presented in a way which references the sketchbook. It reflects the process described by Stephanie Black as “drawing that is generative of ideas and new tangents for enquiry” and which “acts as a record of the thinking and making process.” (2014: 286).

It is an attempt to start with theory as the basis and fuel for the project: primarily, the idea that narrative is “both its art and its discourse” (De Certeau, 1984d: 90), relying on the chapters: ‘The Arts of Theory’ and ‘Story Time’, in De Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life.

My Hypothesis here is that narrative illustration is a fruitful, alternative method of critical, theoretical investigation. I borrow De Certeau’s theories in order to ‘narrativize’ the relationship between practice and theory and use character-driven narrative illustration as an inductive research practice.

Thierry Groensteen breaks the ‘narrator’ in comics into two virtual entities: the reciter, who tells the story linguistically, and the monstrator who tells the story visually (2005). There are links between this inclusion of non-linguistic forms of narration and De Certeau’s concept of “enunciation” (De Certeau 1984b: 33) which he says “we can attempt to apply […] to many non-linguistic operations.”. This idea of ‘enunciation’ allows for ‘silent’ practices such as illustration to ‘speak’ for themselves. Because, even though illustration has a fundamental and characteristic relationship with text, it is not the text itself and so remains a non-linguistic practice.

To explore the relationship between a non-linguistic practice and linguistic theory both in narrative and through narrative, I have turned them into characters. I have personified them by borrowing personalities from fiction and history. Treating practice and theory as if they were in a literal relationship narritivises the discussion, using the sort of non-linguistic practice discussed in De Certeau’s text.

Theory is represented here by a psychoanalyst, loosely based on Freud. This character has written volumes on countless other practices. He is here to turn his ‘discursive mirror’ on the hidden knowledge of the “expert but mute body” (1984b: 42) of illustration practice.

Illustration, as a non-linguistic practice, is represented by Sleeping Beauty: a passive character “lacking language and consciousness” (1984c: 70). Historically, illustration practice is supposed to be the sort of “knowledge which is unaware of itself.” (ibid: 70) in need of an external theory and critic to reveal its internal, unspoken knowledge. However, De Certeau argues that the practice of storytelling, in its many forms, is in fact aware of itself, and is even “an authority on what concerns theory” (1984d: 78). This is why, in this poster, Illustration wakes herself up with a radical act of self-love: flipping the dynamic between the two characters.

I have coined the term ‘Characterification’ in this poster, which is a progression from my previous work where I set Mikhail Bakhtin’s (1984a) idea of the Polyphonic novel against Samuel Butler’s ideas about the “fusion and confusion” (2002: 28) within personal identity. I use these two theories to situate authorial illustration practice as a method of fragmenting the author-illustrator’s identity into several different and warring characters, which become autonomous and move beyond the jurisdiction of their maker (Brace Stevenson 2021).

Charaterification is not just personification, especially since these characters can be generated from existing persons, like Freud. The key aspect of this process, which I want to highlight, is that through becoming characters, abstract ideas can both speak for themselves and engage in a dialogue with each other. They also become subject to narrative twists and character arcs. They can change and mutate, which is how they gain their independence from their origin and their originator, and are able to behave in surprising ways.

There are interesting parallels between Butler and Polanyi’s assertions that both personal identity and personal knowledge are contradictions in terms, respectively. Polanyi talks about the “passionate contribution of the person knowing what is being known” (1962: xxviii) so that knowledge can never be untangled from the individual. This helps justify the personal flights of fancy illustrated here, which has produced the sort of “evidence” De Certeau would describe as “from the imaginary landscape of inquiry” which “can only be fantastic and not scientific.” (1984b: 42), producing the sort of ‘outcomes of artistic research’ which Barret says are “necessarily unpredictable” (2007a: 3).

Bibliography

BAKHTIN, M. 1984a. translated by Emerson, Caryl ‘Dostoevsky’s Polyphonic Novel’ in Problems in Dostoevsky’s Poetics, London: University of Minnesota Press pp.3-46 [pdf] BARRET E. (2007a), ‘Introduction’, in E. Barrett and B. Bolt (eds), Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 1–14.

BLACK, S. (2014) ‘Illumination through Illustration: Research methods and authorial practice’, Journal of Illustration 1:2, pp.275-300

BOLT, B.(2007b), ‘The magic is in handling’, in E. Barrett and B. Bolt (eds), Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 27–34.

BRACE STEVENSON, G. (in press) ‘Exploring Multiple Selves and Polyphonic Voices in Simon Hanselmann’s Megg and Mogg’ in Book Practices and Textual Itineraries: llustrating Identity/ies, Vol 10.

BUTLER, S. 2002., Chapter V: ‘Our Subordinate Personalities’ in Life and Habit, Blackmask Online. pp.37-43, accessed 30 May 2019, http://www.public-library.uk/ebooks/55/87.pdf BUTLER, S. 2002., Chapter V: ‘Personal Identity’ in Life and Habit, Blackmask Online. pp.28-32, accessed 30 May 2019, http://www.public-library.uk/ebooks/55/87.pdf DE CERTEAU, M. 1984b. ‘Making Do: Uses and Tactics’ in The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by S F. Rendall. London. University of California Press. pp.29-42

DE CERTEAU, M. 1984c. ‘The Arts of Theory’ in The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by S F. Rendall. London. University of California Press. pp. 61-76

DE CERTEAU, M. 1984d. ‘Story Time’ in The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by S F. Rendall. London. University of California Press. pp.77-90

GROENSTEEN, T. 2005. ‘The Question of the Narrator’ in his Comics and Narration. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 79-119 [photocopy].

POLANYI, M. 1962. ‘Preface’, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. London. University of Chicago Press, pp. xxvii-xxviii

Tania Esteves Fernandes Cardoso

Transcript

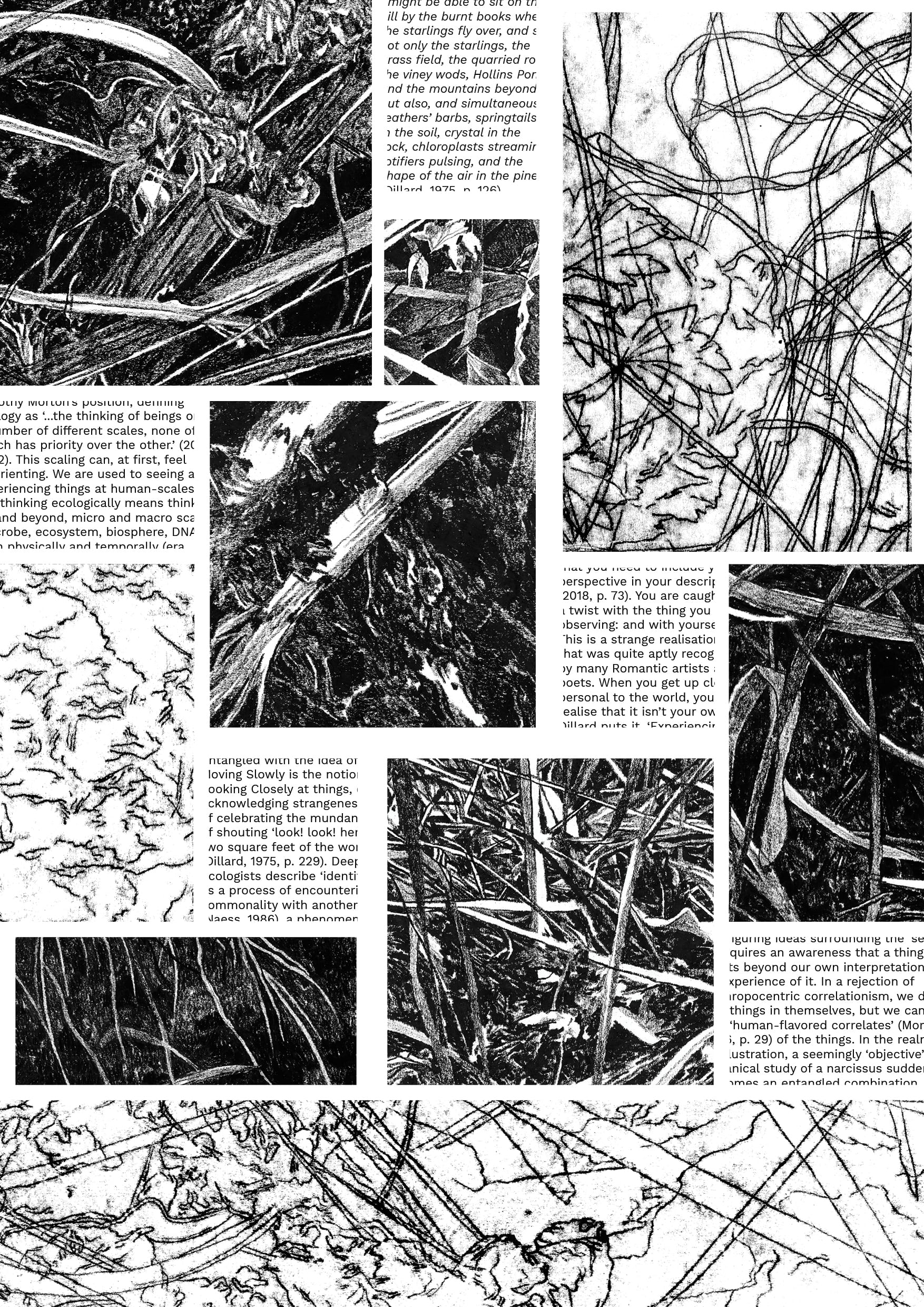

I find myself walking towards an intersection. The street is composed of traditional looking buildings that appear to extend as far as my eyes reach. I keep walking as my path leads me to one of the main squares of the city. I shiver and hold my sketchbook closer. Stopping to investigate I look for textures, sounds, architectural façades, amusing details, weird smells, everyday routines and curious behaviours. I draw for a moment. People catch my eye as I see how the atmosphere of my surroundings changes depending on their acts. These acts also change my perception of the urban landscape.

This small anecdote means to explain how I conduct my artistic practice as research. As I walk through the middle of the crowd, I explore Amsterdam's urban space through the practice of drawing in the entanglement between performance, encounter and documentation. Perhaps unintentionally, this entanglement gives me a specific type of urban knowledge based not only on the senses but also on unpredictability and improvisation. The drawing and further illustration are responses to these encounters with people and with my urban surroundings. These lines in paper, as responses, are testimonies of a moment in space and showcase the ordinary activities that entangled with architecture, moods, and everyday life compose the rhythms of a city.

My artistic practice as research is an on-going process. It associates practices of drawing and illustration with urban exploration. The practice of drawing in situ, what I am showcasing here, provides the illustrator with the opportunity to be seamlessly immersed in their surroundings. This embodied approach allows for drawing to be a form of thinking by doing or to get to know space as you go. Thus, by drawing in urban space, the illustrator skilfully registers sensorial information and gains awareness of place building up from its responses and encounters between people. Through a methodology based on the combination of psychogeographic, site-specific practices of drawing, and graphic journalism, drawing in situ may enhance my urban exploration skills as participant and observer of everyday life. In this way, it works in the fringes between subjective experience and objective documentation. To think about and understand the city in this way is a full experience: the illustrator must equally use the body's movement through space, and the gesture of the hand through paper, as a performance of engagement with space that goes beyond eyesight - a practice of creative documentation.

Ultimately, the practice of drawing in situ as an ability to perceive and express urban space is inherently connected to movement. It may be that drawing is a remarkable act of performance and documentation of the physical world, simultaneously engaging with it and with imagination. Likewise, urban sensation and sensorimotor knowledge may significantly impact the practice of drawing in situ by orienting the illustrator in space and conveying the experience of this interaction in the traces of the drawing. These stand not as duplicates, but as a reality on their own. Due to its on-going nature, a drawing is always scarred by external impact and improvisation. It uses medium-specific elements from illustrated maps, comics and picturebooks, and it never seems complete for it never is. Acknowledging that my practice of drawing in situ is a constant work-in-progress, I suggest that these drawings are syntheses of geographical elements, imaginary constructions and urban experiences placed into a visual medium that intends to be a chronicler of the city.

Evelyn Rynkiewicz & Brendan Leach

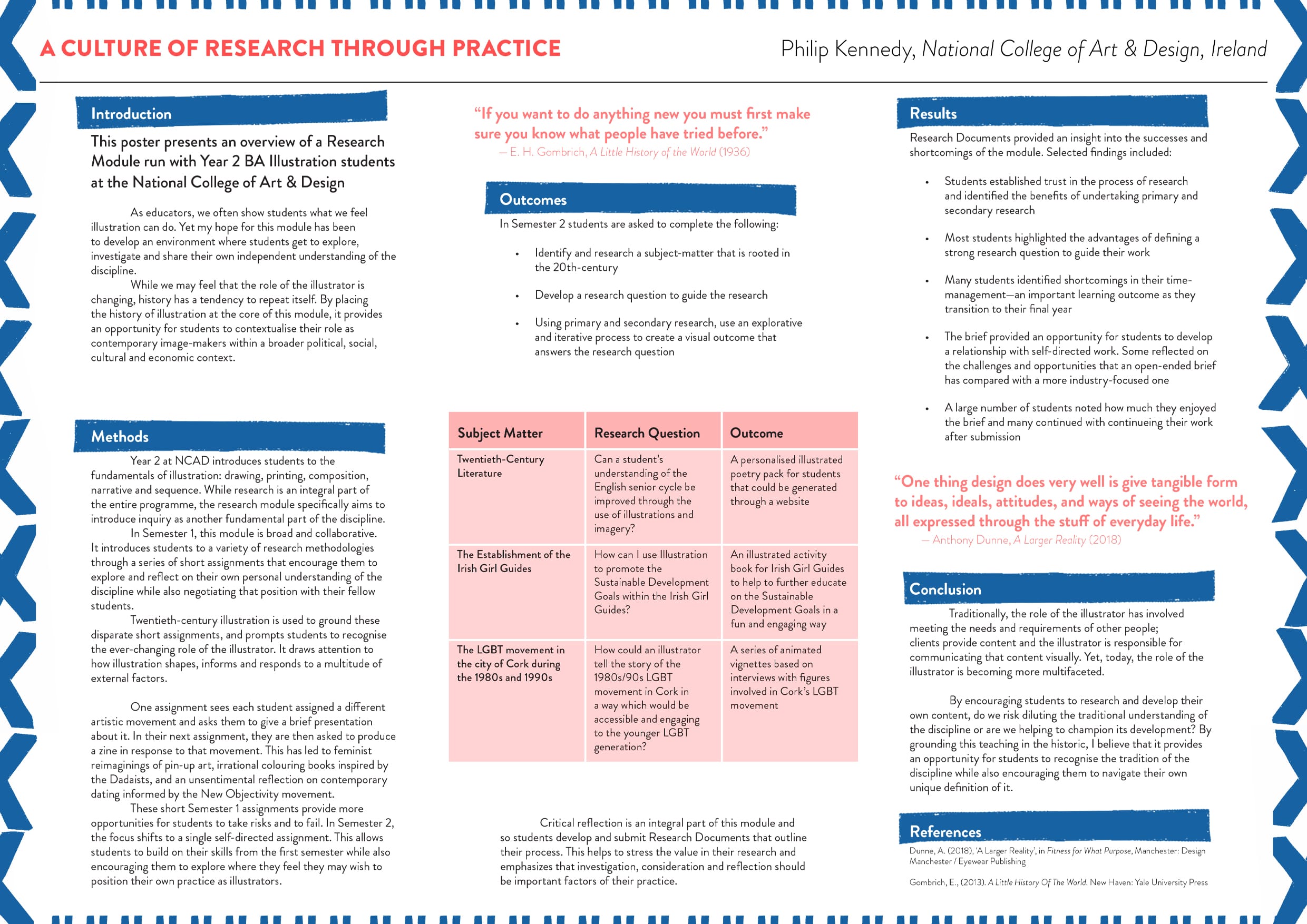

Philip Kennedy

Transcript

Hello, you're very welcome, this is: A Culture of Research Through Practice. My name is Philip Kennedy. I'm an illustrator, a writer and a part-time lecturer at Ireland’s National College of Art and Design

This poster is about a research module I ran with Year 2 students at NCAD for two years from 2018 – 20.

The poster starts with a quote from art historian E. H. Gombrich. It says: “If you want to do anything new you must first make sure you know what people have tried before.” I think this is something that is often overlooked in illustration education. And so, the module aims to get students to use the past as a starting point for making something new. For me, I try and do that by developing an inquiry environment in the studio for my students. The module runs over two semesters and is split into two somewhat contrasting parts:

- Semester 1 – broad and collaborative

- Semester 2 – specific and independent

Semester 1

— Introduces students to a variety of short weekly research assignments.

The outcomes of which are broadly almost trivial; they act more as prompts for discussion and debate around what illustration is. For example, what makes illustration different to art, say or graphic design. What function does an illustration serve? Stuff like that. One of the hopes is that students develop a stronger ability to recognise both what an illustration says and also how it says it.

The final assignment, for example, this semester, sees them produce a zine based on a cultural or artistic movement in the 20th century.

This has led to things like:

- Meditations on contemporary rural identity — after looking at how the modern urban experience shaped the Harlem Renaissance

- The role, value and legacy of counter-culture movements based on psychedelia.

- The idea of value (in terms of economics, power and beauty) that can be seen through the American Federal Art Project.

You can see a few more examples of these listed the poster.

These movements introduce a broader context for the work that they produce and forces them to ask questions on the role of the image in a historical, political, social or cultural context.

Semester 2

– Things get more specific and their project spans the full semester. The starting point for this remains the 20th century but the main hope here is to give students a prompt that encourages them to consider the function of their work within a contemporary context. This is the stage, where I really emphasis that problem finding is just as important as problem-solving. Students present their ongoing research and then we spend quite a while developing a research question; really getting to the core of their interest. This encourages them to think more about what their work says rather than how they might say it.

Many draw on their personal interests and I believe that the work done in semester 1 typically gets them to be more ambitious in their scope.

There are three examples there on the poster of the types of projects produced. To add two more examples: we had one student who was fascinated with 20th-century celebrity pathology, and that led them to produce an illustrated time-based story that played out over social media that used the absurdity of celebrity pathology to speak about our current relationship with social media and social-media influencers.

Another student had a personal experience in Cambodia and they used the brief as an opportunity to learn more about the Khmer Rouge regime; eventually, leading to them asking how an illustrator might develop an affordable and meaningful resource that could help to communicate social issues to teenagers in the country? The resulting outcome was distributed freely at a youth camp where she had volunteered that previous summer.

So, in conclusion, the semester 2 brief presents the illustrator as not just 'content producer', but also as 'content definer'. I believe that by allowing this module to sit alongside more traditional client-focused briefs, it allows the student an opportunity to consider the role of the illustrator as being more multi-faceted.

The question is: by researching and developing their own content, is their a risk that we dilute a traditional understanding of the role of the illustrator? Personally, I feel that self-direct project work is important and speaks to the multi-disciplinary nature of the contemporary illustrator, but I believe that by placing the teaching within a framework that recognises history, it provides an opportunity for students to recognise and reflect on the tradition of the discipline while also navigating their own unique personal and contemporary definition of illustration.

I've been Philip Kennedy. Thanks very much for listening. Stay safe.

Jamie Mills

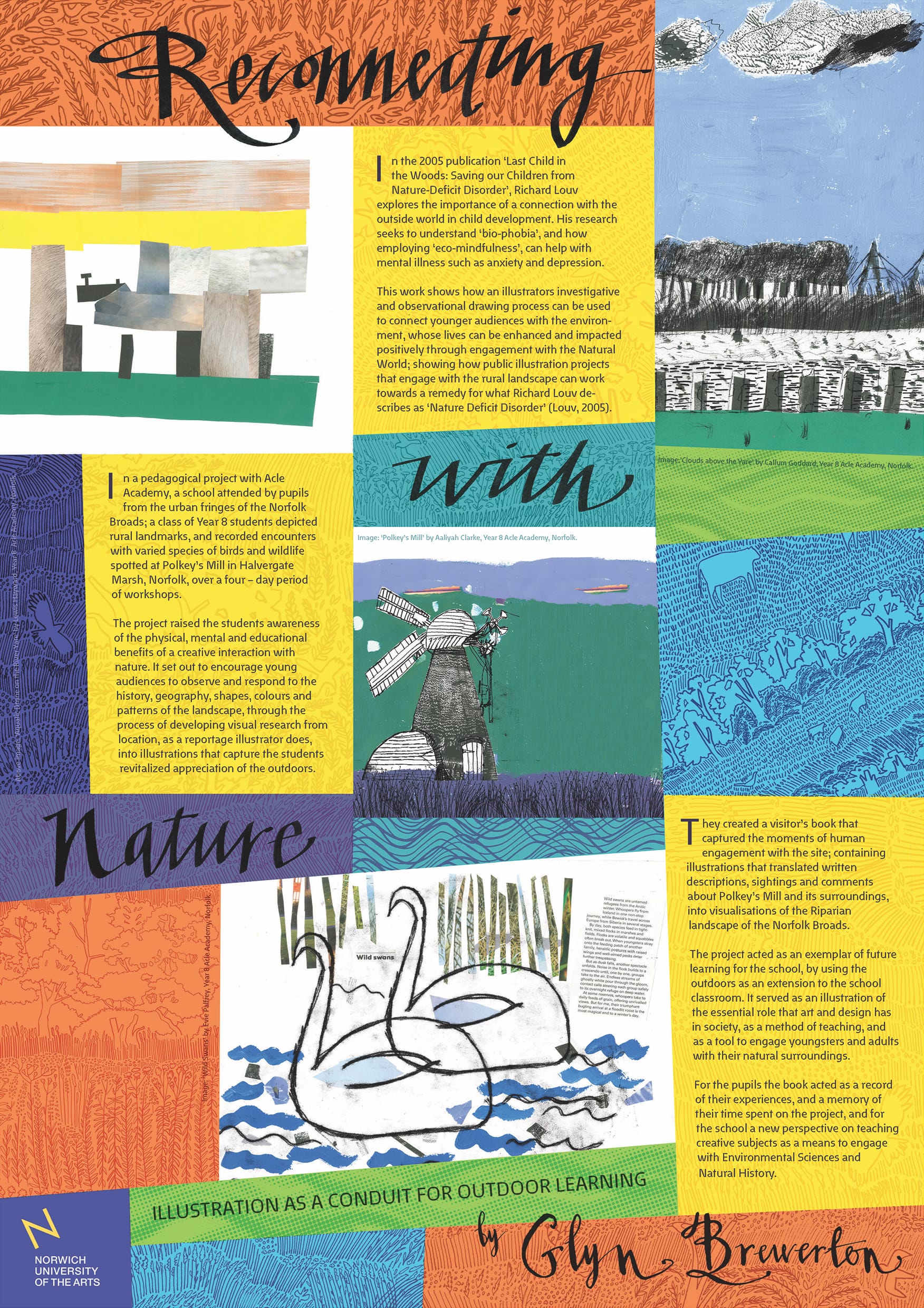

Glyn Brewerton

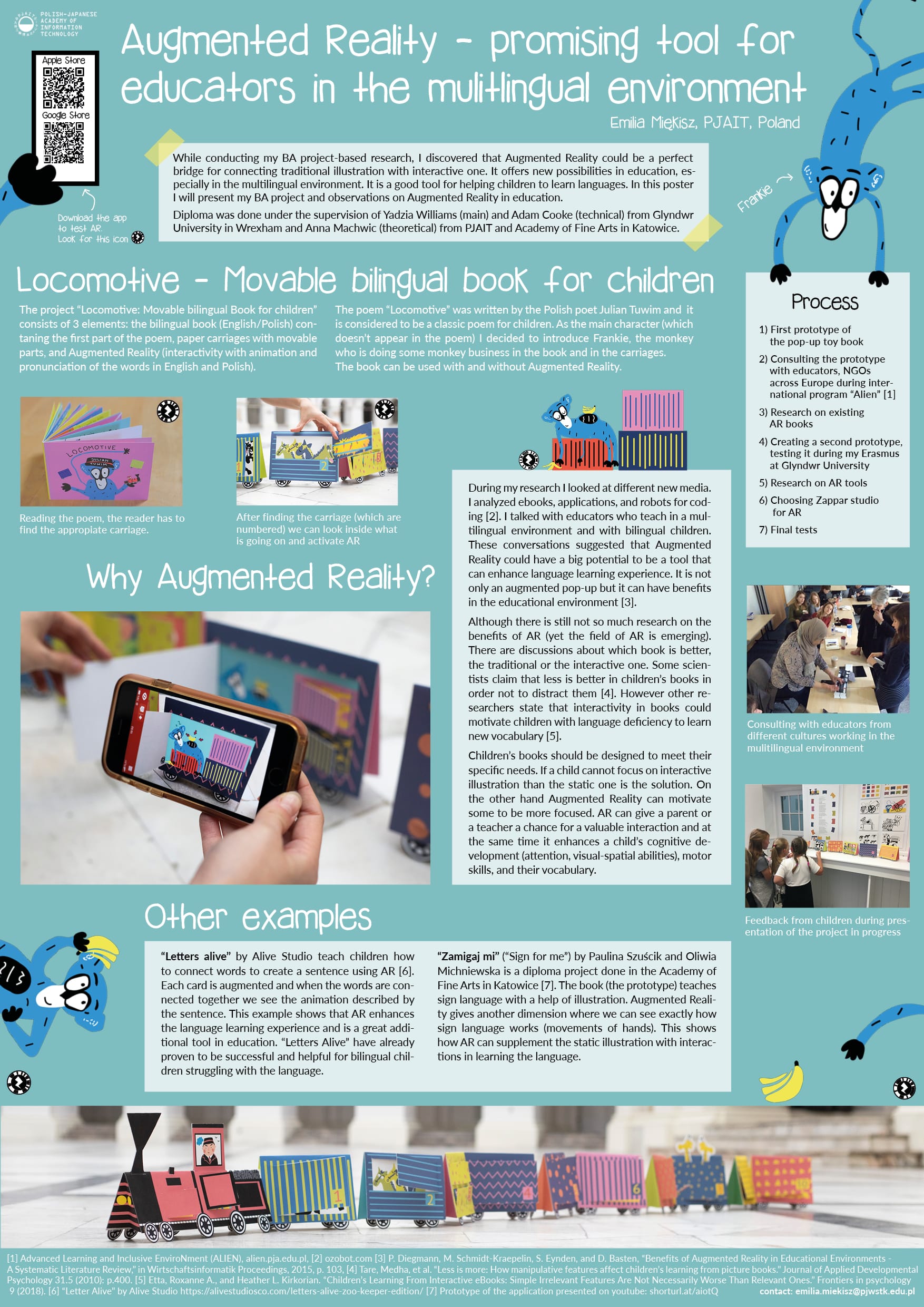

Emilia Miękisz

Transcript

Hi everyone, Dzień Dobry. My name is Emilia Miękisz and I am a MA student at the Polish Japanese Academy of Information Technology in Warsaw, Poland. In this poster I want to present to you my BA diploma project “Locomotive - Movable Bilingual Book for children” and why I think Augmented Reality is a promising tool for educators in multilingual environment. My poster is also augmented. In the upper left corner you can see the QR codes, where you can download the app and test it right away in the poster. If you have any questions you can contact me on my mail or during the conference. Hope you enjoy the poster and interactive elements.

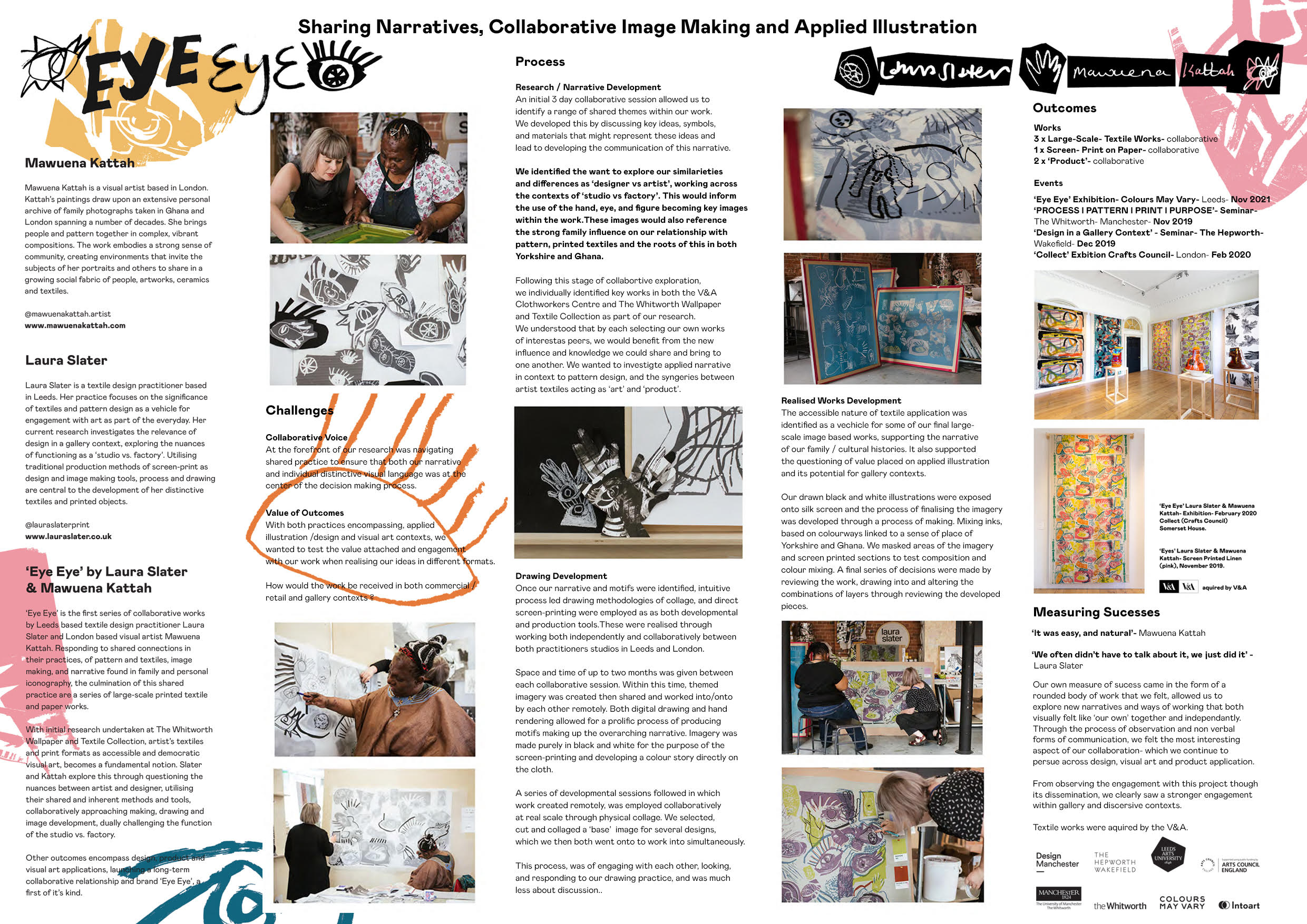

Laura Slater

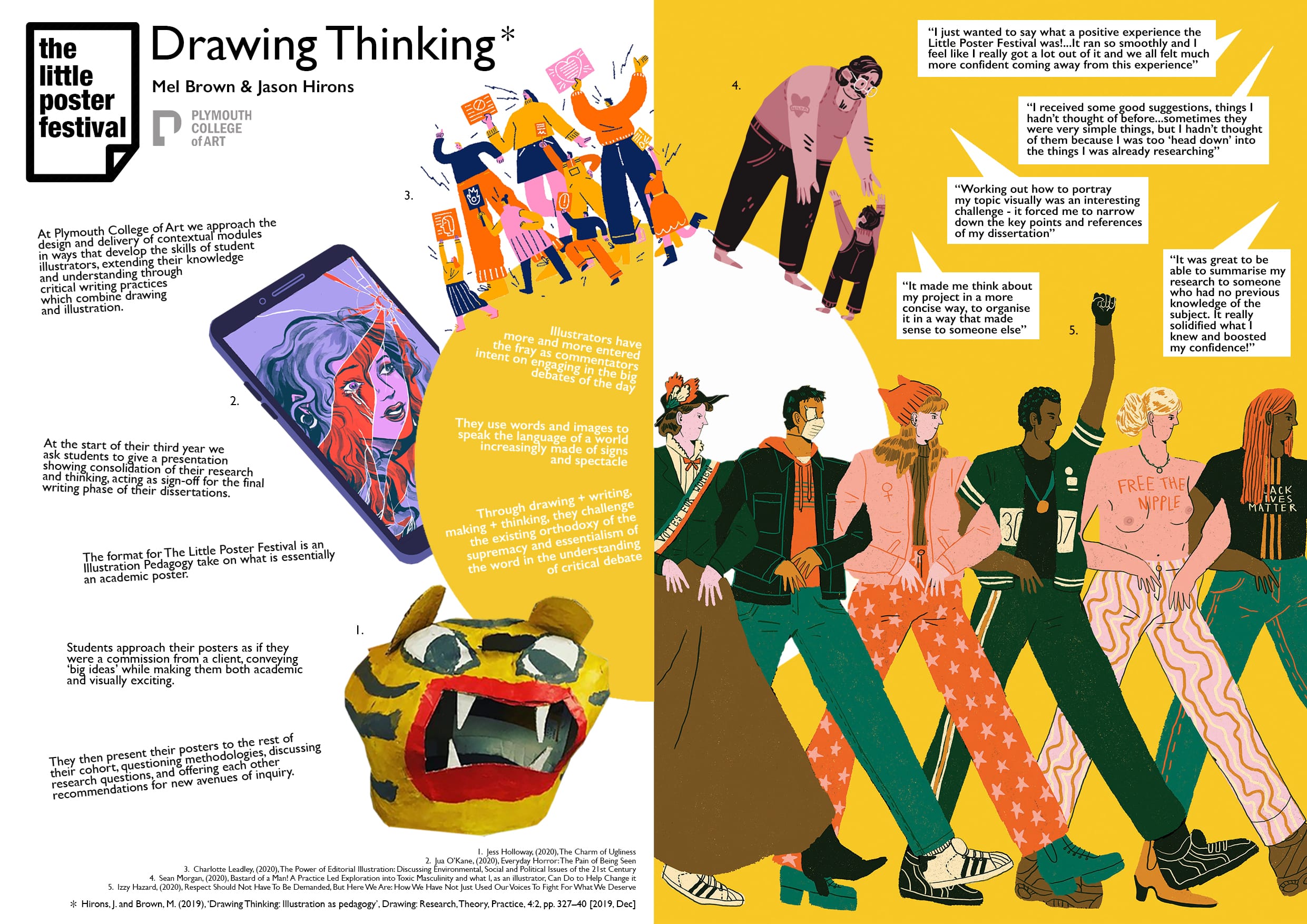

Mel Brown & Jason Hirons

Transcript

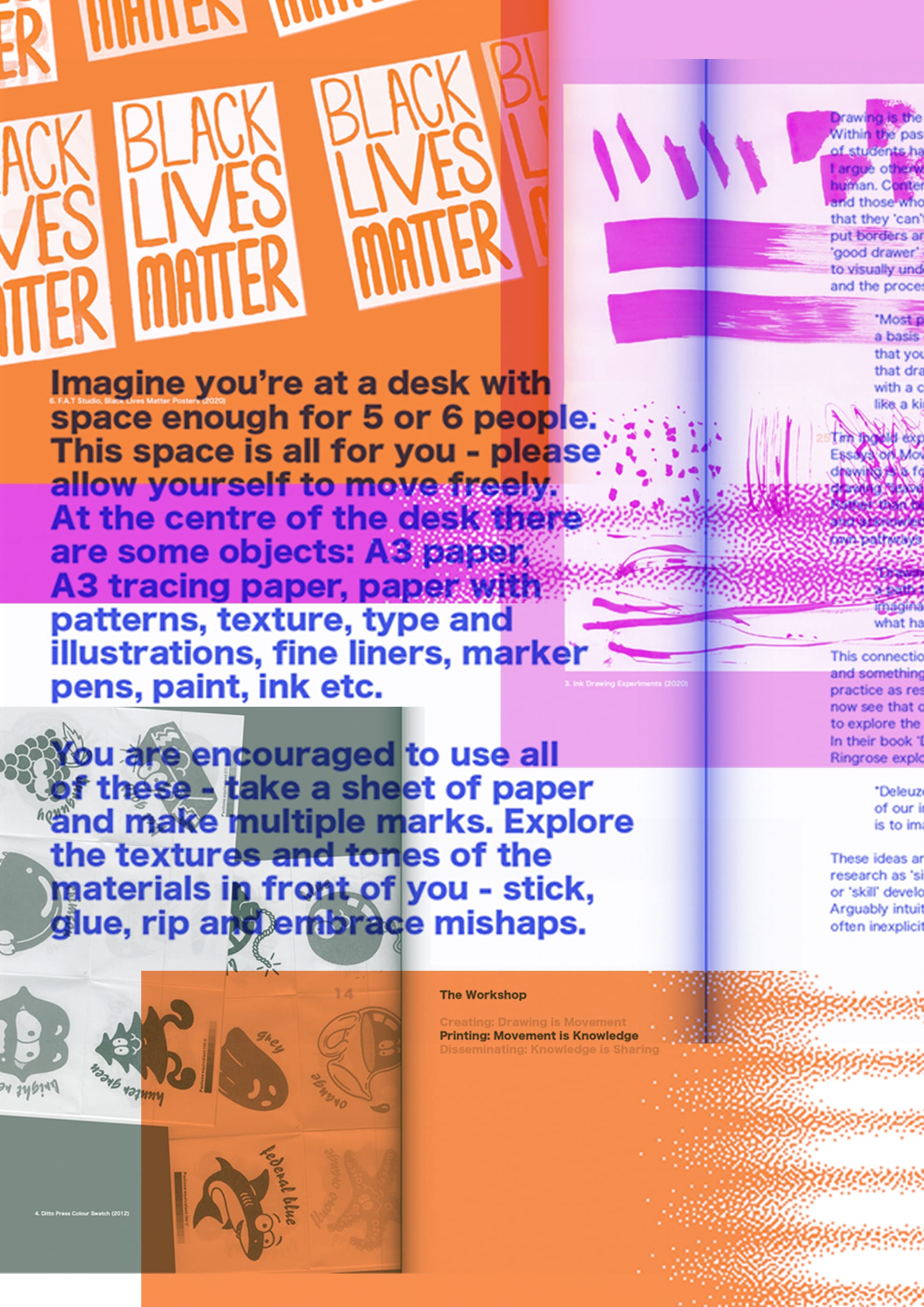

The Little Poster Festival came out of a requirement for students to do a work in progress presentation on their dissertations.

We had been encouraging more creative illustration-led responses for a while, and that, together with large class sizes and constraints on time, led us to look for something different.

We had already been talking about illustration as a method and had them creating reflective journals, the great editorial race module, getting them to design their journey through their degree as a board game, and introducing the artefact option for the dissertation, and so the logical step for the work in progress presentations was an academic poster with a difference... one that was performative, critical, responsive, and playful.

We drew up some ground rules, showed them examples the kind of academic posters we wanted them to subvert - this involved lots of photographs from the internet of students proudly pointing at extremely dull looking posters at conferences - and gave them some guidelines as to what must be covered, such as theories, frameworks, case studies etc.

We’ve run it twice so far and the presentations are so much more informative and rigorous than getting them to sit in groups sharing PowerPoints. They have fun, they get noisy, and they get genuinely useful feedback as part of a kind of festival of ideas.

As tutors we get to see our students express themselves as illustrators confident in their practices and in their developing knowledge of a research question. Such has been the success of the little poster festival that we couldn’t imagine going back to the old way of doing these presentations, and certainly the feedback we’ve had from students shows just how valuable it is to approach the dissertation module as one where they are thinking through making, drawing and writing through practice.

Gary Embury

Hayfaa Chalabi

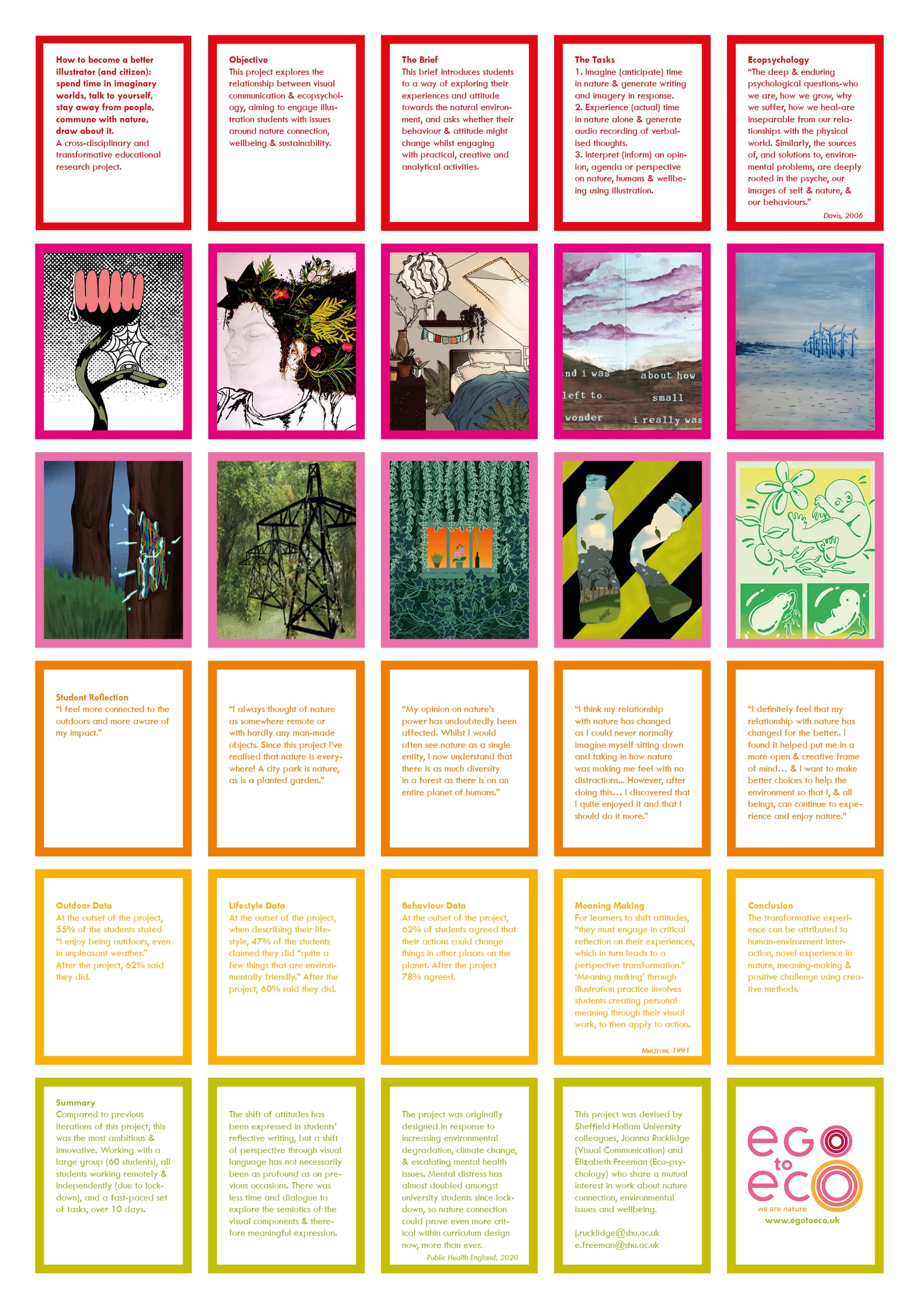

Joanna Rucklidge

John Miers

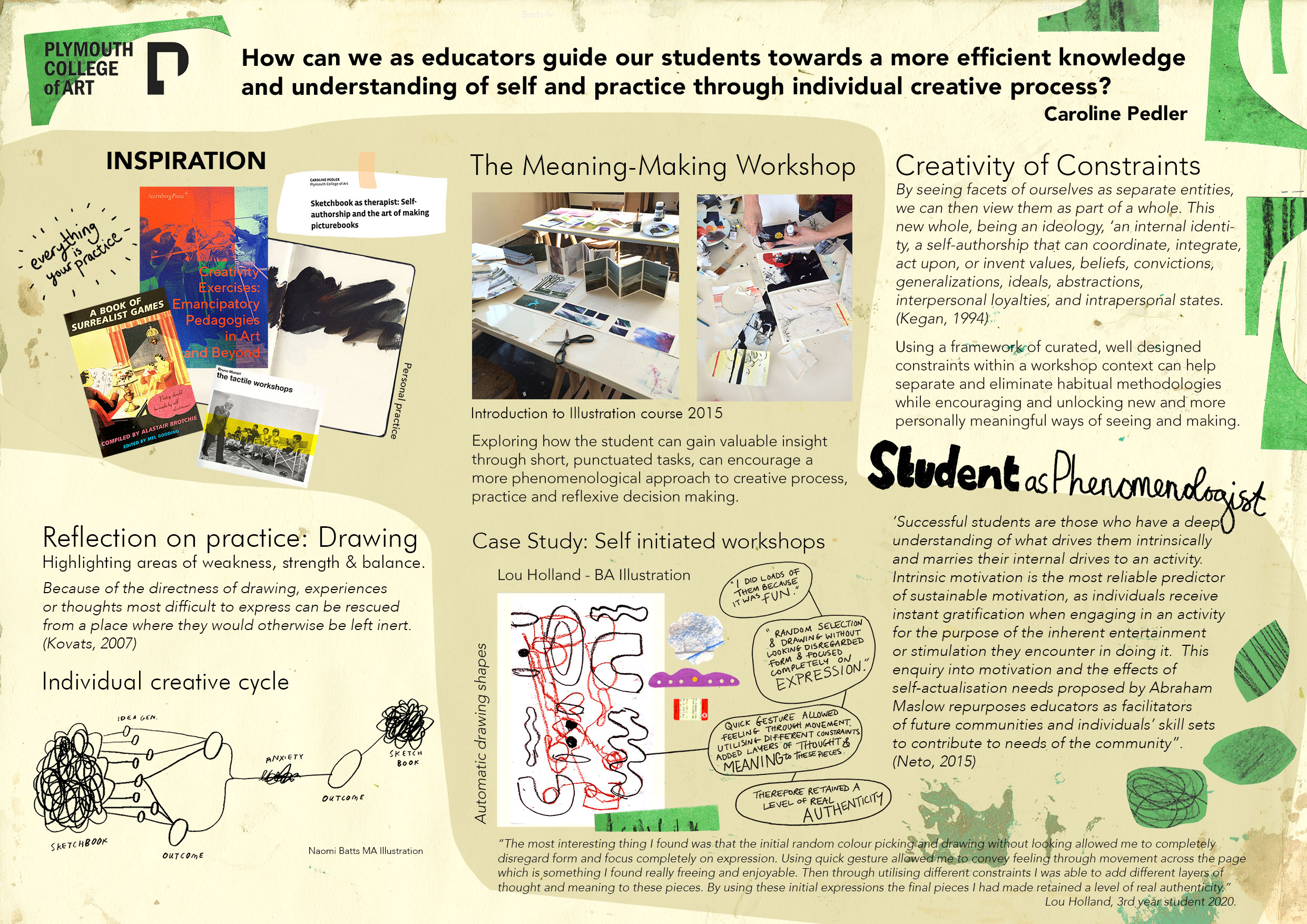

Caroline Pedler

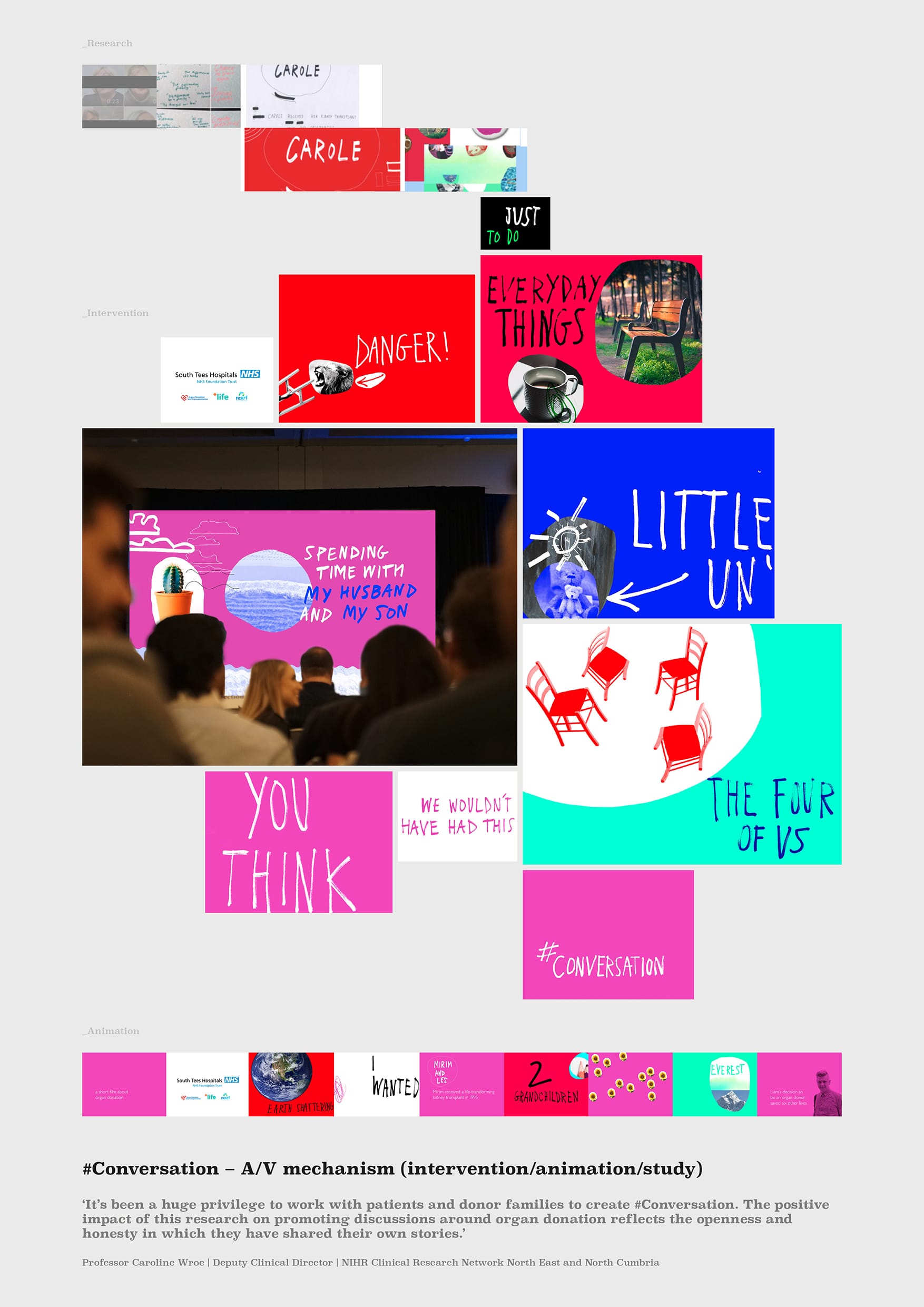

Transcript

Illustration has become an expansive and visually amorphic industry and while teaching Illustration in higher education I have noticed an increased focus around the styles of well-loved illustrators coveted by students, indirectly encouraging a more decorative and less meaningful approach to artwork and a failure to conceive the steps taken to achieve such results. So, my question is how can we as educators engage these students more efficiently in the illumination of their own individual voice, rather than aspiring to the voice of another.

There are various ways of guiding a student to success as an illustrator, practically and critically through the briefs they are set within higher education, but often this student can still be unaware at graduation (and even at postgraduate level) of how to fit their personal ideologies and identities into the work they create for university modules and can therefore view personal work and course specific work as separate entities. Looking to exterior visual and social sources for validation and inspiration which at best produces a cohort of copycats, and at worst causes creative paralysis through inappropriate comparison.

In my essay Sketchbook as therapist: Self-authorship and the art of making picturebooks, I propose self-authorship (Kegan, 1994) as a framework to enable the illustrator to better understand personal practice, engagement and visual identity through critically informed decision making based on one’s internal beliefs and experiences.

This research presentation is a continuation of that essay and takes inspiration from the valuable reflection and meaning I gathered from a selection of tasks I set myself as an MA student in 2009 on the Illustration – Authorial Practice course at UCF. My MA was a journey of failure, success and discovery around personal practice and the development of an authentic visual language. The research I did there has been fundamental in creating a strong authorial foundation and continues to enlighten and enable a higher level of insight and authenticity in the work I create and communicate today, while also building a methodology that I can return to in moments of overwhelm or creative block.

I would like to pass these creative insights and experience forward to the students I have been teaching now for a decade, helping them find a way to cut through the paralysis of celebratory virtuosity, helping them move further towards an authentic illustrator’s voice.

So how do we do that? And how do students find meaning in making via the creative tasks given?

‘Through ‘meaning-making’, people are "retaining, reaffirming, revising, or replacing elements of their orienting system to develop more nuanced, complex and useful systems". (Kegan, 1980)

Or in more simple terms is the process of how people understand, or make sense of life events, relationships, and of the self. Where both understanding and interpretation is present, making connections between new and existing knowledge.

I have already begun to research, design and curate tasks that encourage immediate and spontaneous results and remove the known outcome. I intend for the tasks to be fun, yet informative without too much thought or intention. Meaning that logging and reflecting patterns of individual behaviour and intuitive action is possible, while enabling capacity of the student to translate purpose, feeling or idea into a physical form more organically. Then slowly building a map of ideologies, unique ways of seeing while fostering creative resilience within their practice. In short, to reflect on ‘why they make art’ (Grove, 2018).

Creative constraints will be tested and implemented within these tasks as a way of producing more creative and authentic outcomes while also shaking habits and again, unlocking new ways of seeing.

This research is in its infancy but it comes from a long period of noticing and taking note of the barriers and blind spots that some student illustrators face regularly and through a series of well designed, curated tasks or workshops, I hope I can begin to empower these student illustrators to make decisions based on their individual capacities, inclination and beliefs and towards an intentionally more effective and meaningful life as an illustrator.

And I would like to thank Naomi Batts and Lou Holland for sharing their own work with me and aiding in the visual communication of the research in this presentation. Thank you.

Transcript

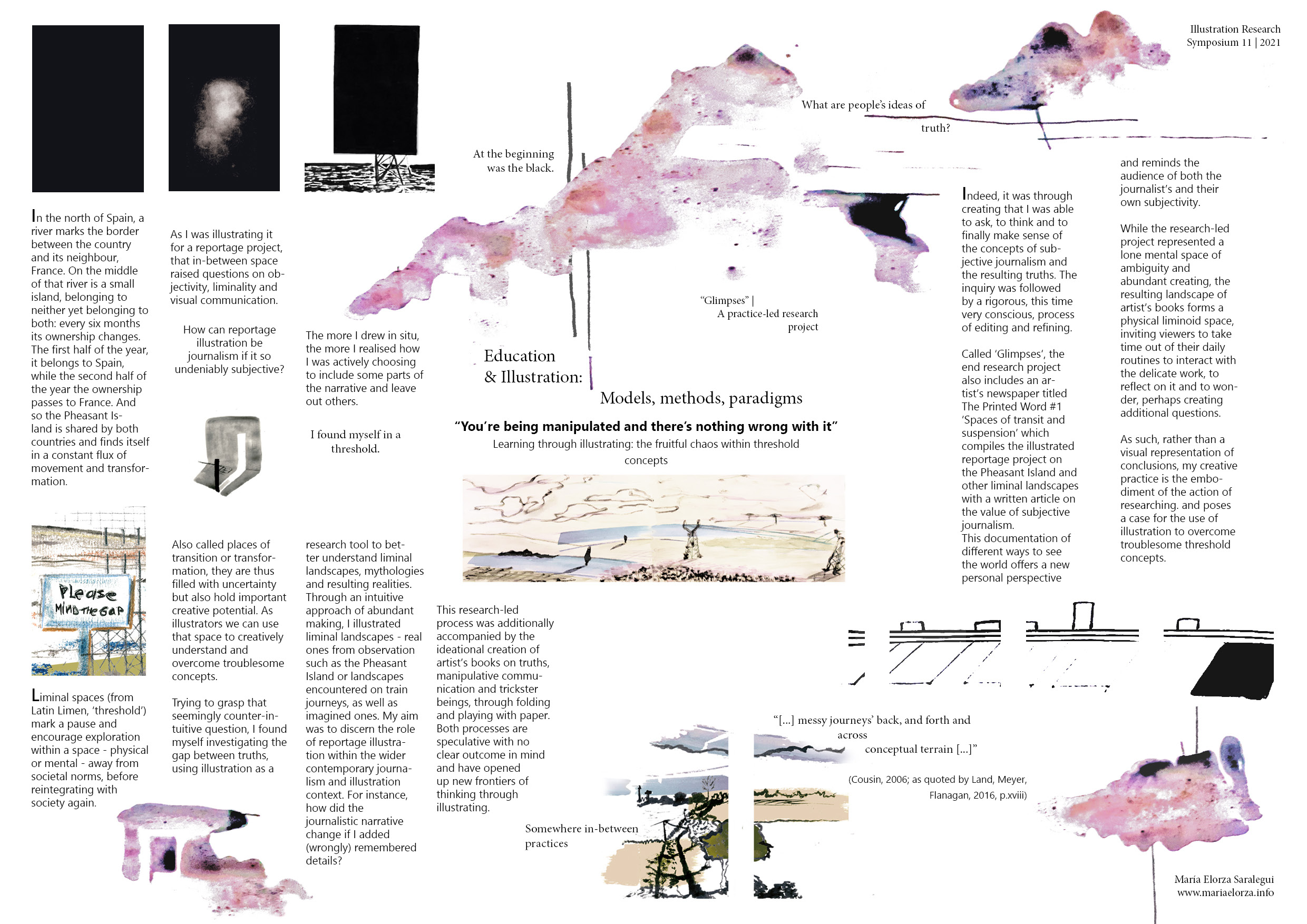

Illustration often feels like sand that I'm trying to get a hold of and yet can never quite grasp. Sometimes it feels mentally demanding, as if I'm pushing through walls that I don't properly see. And so I find that for me illustration works best with an approach of intuitive making, being guided rather than actively knowing where I'm headed towards. It becomes a speculative play of continuous searching - until that exact moment when in the middle of creating, of illustrating, the process suddenly feels right and makes sense. A door opens up and I feel myself understanding whatever I was trying to research, or at least some aspect of it.

Illustration helps me make the most of the creative potential within "liminal spaces, within borders or waiting areas, be they physical or mental.

It's a learning through abundantly making within thresholds. In the case of the following research-led inquiry which results in a collection of artist's books, I was trying to make sense of the value of subjective journalism and how this fits in the contemporary discourse around truth narratives. It started with a seemingly simple question on people's ideas of truths and evolved to become an exploration into manipulative communication, mythologies and liminal changes - represented through the constant shifting of a river island in the South of Europe, which the first half of the year belongs to Spain while the second half of the year it's owned and taken care of by France.

This island is the foundation of a reportage project titled "Spaces of transit and suspension". Published in an artist's book in form of a newspaper it belongs to a bigger collection of artist's books.

Alongside the question whether we place too much value on objectivity, other concepts emerged, some more troublesome than others. In an era of fake news and alternative facts, stating that subjective journalism holds value raises of course questions on its potential danger to democracies. And yet, illustration as journalism works, despite or rather precisely because of its more visible subjectivity.

A physical liminoid space, so relevant to the context of the current times, is created through the installation of artist’s books, inviting viewers to take time to interact with the work, to reflect on it and to question pre-established beliefs. A space to pause and to think. Drawing from familiar "real" landscapes, the books take you on a journey somewhere in-between where the mind is allowed to wonder. Illustration hopefully becoming a tool to not only research but also to encourage conversations, understanding, and empathetic reflection.